Now, this guide will be quite long so I will go through a little list to let you know what you will be learning:

- What it takes to learn Japanese

- Internet Resources

- Books, Apps and other Resources

- Crash course into Japanese

What does it take to learn Japanese ?

First of all, the internet is a vast place and you will be able to find a lot of resources. I do think that with a lot of effort you could actually learn Japanese by just searching some random posts but I don't recommend it for 3 reasons:

Too much junk

One of the first things you will notice is that the internet is filled tutorials and info. That is something good but not for actually learning. If you want to learn Japanese you should stay away from randomly look things up. You should learn things in a structured way so that everything makes sense.

Few things make actually sense

Most of the things that you will find on the internet make therefore little sense most of the time. And you will end up discouraging yourself to learn Japanese. At the end you will always feel like you are not making any progress.

You never feel like learning something

All this contributes to this feeling of not really learning anything. So read a little more and I will give you a structured strategy where you will go learn something and leave gracefully without disrupting your learning flow.

Lets dive in. What are the key parts that you actually have to focus on ?

Japanese is a language like any other and you can definitely learn it by looking at it like any other language:

- vocabulary

- grammar

- writing and reading

If you do not have vocabulary, you can not make sentences if you do not know the grammar you can not build the sentences and if you can not write or read you can not progress in your learning process. Basically they all depend on each other. So now that we know what it takes let us look at the structured strategy that you need will need to learn Japanese.

Japanese really is a fascinating language because it is actually quite simple. Once you learn Japanese you will feel like most sentence actually sound elementary school like.

When you learn Japanese you will want to follow this cycle:

- Memorize vocabulary

- Look up the writing for that vocabulary

- Read up some grammar

- Build Sentences

1 Memorize Vocabulary and Look up the writing

We will learn writing Japanese further down but for now I recommend these resources to memorize vocabulary and look up the writing:

Japanese Pod 101 - They have a list of the 2000 most used words

Wikipedia - This article features 1000 basic Japanese words.

Kodansha Dictionary - One of the best Japanese to English dictionaries out there

Small word on the Kodansha Dictionary (Resume):

A comprehensive, communicative, and practical guide to using Japanese, Kodansha's Furigana Japanese Dictionary is an invaluable tool for anyone with an interest in the Japanese language. It has been edited with the needs of English-speaking users in mind, whether students, teachers, business people, or casual linguists, and special care has been taken at each stage of its compilation including the selection of entry words and their equivalents, the wording of the detailed explanations of Japanese words, the choice of example sentences, and even its functional page design to maximize its usefulness.

If you do not have vocabulary, you can not make sentences if you do not know the grammar you can not build the sentences and if you can not write or read you can not progress in your learning process. Basically they all depend on each other. So now that we know what it takes let us look at the structured strategy that you need will need to learn Japanese.

Japanese really is a fascinating language because it is actually quite simple. Once you learn Japanese you will feel like most sentence actually sound elementary school like.

When you learn Japanese you will want to follow this cycle:

- Memorize vocabulary

- Look up the writing for that vocabulary

- Read up some grammar

- Build Sentences

1 Memorize Vocabulary and Look up the writing

We will learn writing Japanese further down but for now I recommend these resources to memorize vocabulary and look up the writing:

Japanese Pod 101 - They have a list of the 2000 most used words

Wikipedia - This article features 1000 basic Japanese words.

Kodansha Dictionary - One of the best Japanese to English dictionaries out there

Small word on the Kodansha Dictionary (Resume):

A comprehensive, communicative, and practical guide to using Japanese, Kodansha's Furigana Japanese Dictionary is an invaluable tool for anyone with an interest in the Japanese language. It has been edited with the needs of English-speaking users in mind, whether students, teachers, business people, or casual linguists, and special care has been taken at each stage of its compilation including the selection of entry words and their equivalents, the wording of the detailed explanations of Japanese words, the choice of example sentences, and even its functional page design to maximize its usefulness.

Hold your horse for a second, don't go overboard now. The point is to learn those words and their writing so take it easy. Learning 5-10 a day is completely enough.

2 Loop up the writing

The previously mentioned resources contain the writing you need and we will learn how to write Japanese further down, so hang in there.

3 Read up some Grammar

When you read grammar you will want to focus on:

Particles - they connect your words in Japanese

Verbs - Japanese have different versions of Verbs (polite+, polite and informal)

Adjectives - they behave a lot like verbs in Japanese

I recommend these resources:

Human Japanese -> Is probably the most powerful software out there

- Human Japanese Beginner

- Human Japanese Intermediate

- Human Japanese Combo Pack (best option)

- Human Japanese for Mac

Human Japanese teaches you from beginner to intermediate. They have another program for intermediates to more advanced Japanese.

Once you go through these, you will be able to build first simple sentences and then more and more complex sentences.

Hold your horse for a second, don't go overboard now. The point is to learn those words and their writing so take it easy. Learning 5-10 a day is completely enough.

2 Loop up the writing

The previously mentioned resources contain the writing you need and we will learn how to write Japanese further down, so hang in there.

3 Read up some Grammar

When you read grammar you will want to focus on:

Particles - they connect your words in Japanese

Verbs - Japanese have different versions of Verbs (polite+, polite and informal)

Adjectives - they behave a lot like verbs in Japanese

I recommend these resources:

Human Japanese -> Is probably the most powerful software out there

Once you go through these, you will be able to build first simple sentences and then more and more complex sentences.

Books, Apps and other Resources

So far you have the structure and the resources to make to it to an intermediate Japanese level believe it or not. But as you progress you will find that real material is indispensable. I already mentioned a dictionary and an app that will help you a lot. If you had to choose, go with App first (it comes with packed with grammar, vocabulary, sentences, writing and reading exercises). Other well known and respected resources I recommend are:

|

| Best Selling Japanese learning books out there |

|

| Excellent for learning how to write |

|

| Kodansha Dictionary |

|

| Human Japanese |

There really is no need for more resources. If have these four, you have all you need to make it to an advanced Japanese.

Crash Course on Japanese

Congratulations on making it this far. I'm sure a lot of what you read this far seem dead simple but that really is all you need get from Zero to an advanced Intermediate Japanese. But I don't want to let you out the world without teaching you some actual Japanese. And that is the purpose of this section. You will learn first how to write, then an intro about particles and verbs and finally some more in depth grammar. So let start.

Writing Japanese (Kana & Kanji)

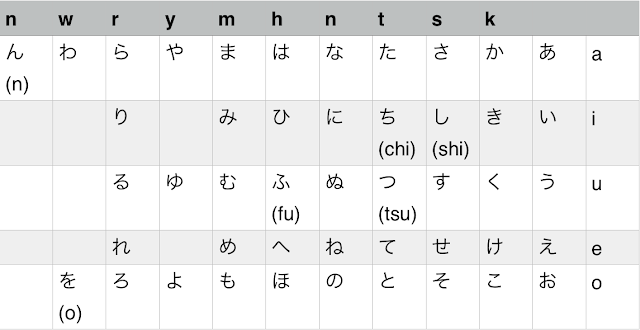

As you might know, the Japanese writing system is divided into three systems: Hiragana(ひらがな), Katakana(カタカナ) and Kanji(漢字). Hiragana and Katakana are known as Kana. The written out version of the Kana and Kanji is known as Rōmaji. Avoid using Rōmaji except for the beginning of your Japanese learning process because it is not accurate and Japanese people don't understand Rōmaji either.

The Kana writing system is made up of phonetic syllables. The syllables are created by combining a consonant with the five vowels. For example, the “ka-series” is created by combining “k” with the five vowels. This results in “ka”, “ki”, “ku”, “ke”, “ko”.

For all the upcoming lessons I will be using either Hiragana or Katakana in the examples. I will provide the Rōmaji version below to aid you a little during this learning curve.

Hiragana(ひらがな)

The Hiragana system is the phonetic version of the language. The language uses these syllables to form and pronounce all their words.

You will have to memorize these syllables. In order to do so, you have to write them out several times until you remember them completely. Once you memorize them, they will stick easily.

I recommend you use a college block and then write a whole line of "ka's" and then you move on to "ki","ku", "ke", "ko", ect.

example:

かかかかかかかかかかかかかかかかかか

As you can see, the wa-series series has only two syllables. The wo “を” is used exclusively as a particle in grammar. Further down, I will write more about particles and the syllable “を”.

The stroke order is important to make your writing more fluid and give the symbols the correct form. You start from the top left and work your way down to the bottom right. From left to right and from top to bottom.

When writing Japanese symbols, you have to imagine a square. All symbols have to fill that square.

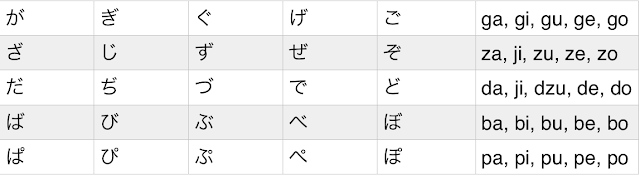

The two small lines (quotation mark like) are called dakuten(濁点).

When you add dakuten to the ka-series, these syllables become “ga”, “gi”, “gu”, “ge”, “go”.

When you add dakuten to the sa-series, these syllables become “za”, “ji”, “zu”, “ze”, “zo”.

When you add dakuten to the ta-series, these syllables become “da”, “ji”, “dzu”, “de”, “do”.

When you add dakuten to the ha-series, these syllables become “ba”, “bi”, “bu”, “be”, “bo”.

The small circle on the upper right corner is called handakuten(半濁点).

When you add it to the ha-series, these syllables become “pa”, “pi”, “pu”, “pe”, “po”.

When you add it to the ha-series, these syllables become “pa”, “pi”, “pu”, “pe”, “po”.

Special Rules

Now that we know all the syllables, we will introduce some special rules.

Double consonant

In Japanese it is common to double a consonant and this is done through the use of a small “tsu(つ)”.

The consonant that comes after the small tsu(つ) is doubled.

There is an exception to this rule. If you want to double the consonant “n”, you don’t use the small tsu(つ). In this case, you use the lone “n(ん)”.

どんな

donna

Combined syllable

You can combine the syllables that end in “i” with a small “ya”, “yu”, “yo” to form a combined syllable.

You can attach the small characters of ya, yu, yo to the characters of ki, gi, shi, ji, chi, ni, hi, bi, pi, mi and ri.

Once you finish this, you are done with Hiragana(ひらがな). You have all the rules you need to become a master in reading and writing it. If you want to improve your new skill, you can go and search the web for some child books in Hiragana(ひらがな). A nice title to start with is "Saru kani Gassen"(さるかにがっせん). You won't be able to understand what you read just yet but you will be able to read it.

The links below contain valuable legal websites with Hiragana(ひらがな) texts, stories and fairy tales. Some of these websites offer even a translation and some vocabulary of the text.

- http://hukumusume.com/douwa/betu/jap/05/01.htm

- http://hukumusume.com/douwa/betu/yuumei_01.html

- http://life.ou.edu/stories/

- http://www.asagaku.com/index.html

If want you to download legal free Japanese literature you can visit Aozora Bunko. This site offers free books of authors that died 100 years ago. You can download those books in different formats. You can work your way through the entire website with google translate and find all sorts of books. The books have some Kanji but they have furigana(small hiragana symbols) on top so you can read the Kanjis without knowing them.

My favorite book is a classic of japanese child literature. It was written by Kenji Miyazawa and is called "Night on the Galactic Railroad". You can find it here:

DOWNLOAD EBOOK

Try to improve your reading speed and getting used to reading Hiragana(ひらがな).

In the coming lesson, we will introduce you to katakana(カタカナ) and some vocabulary(ごい) so you can start understanding the basics.

You have to have special care with the characters for “shi” and “tsu”. They are very similar and easy to mix up.

Kanji(漢字) structure

As you can see in the image, the stand alone pronunciation is “hito(ひと)” and the attached pronunciation is “jin(じん) or “nin(にん)”. To show you how kanji behave I used it in an example.

Grammar

With this, you can take any Japanese verb conjugate it and use it. That’s great you have archived a milestone.

This time the vocabulary is pretty much self explanatory. The only thing I would like to explain is that the prefix “ko(こ)” comes from “kodomo(こども)” which means kid. It is added at the beginning of an animal to make it a baby animal.

Questions

Numbers

Great, so now we can count from 1-10 but what comes next ?

Vocabulary

It is important to note that the block that actually moves is the "place & NI" block. The rest stays as it is.

In the case of the particle "wo", it is a simple extension of the verb. Your object is attached to the verb with this particle. It means that you don't move the "verb block". To illustrate this, here is an example:

せんじさんは にほんに ほんを よみます = Senji-san ha nihon ni hon wo yomimasu

(Senji reads a book in Japan)

にほんに せんじさんは ほんを よみます = nihon ni Senji-san ha hon wo yomimasu

(Senji reads a book in Japan)

Now, this is actually a bit beyond just telling direction but it this shows you how the block nature applies to the particle "wo".

Our last Particle

We always say what belongs to us and what does not. In english, we usually use either the apostrophe " 's " to do so or "of".

There are other options as well. But in Japanese, there is only one way to show possession and that is with the particle NO.

In the coming lesson, we will introduce you to katakana(カタカナ) and some vocabulary(ごい) so you can start understanding the basics.

Katakana(カタカナ)

If you read through the previous lesson and learned how to read and write Hiragana(ひらがな), then this lesson will be easier for you. Below is the chart with the basic characters. As you can see, Katakana(カタカナ) uses the same syllables. The only difference, is that they are written differently.

Katakana(カタカナ) is mainly used to write out foreign words. The easy thing about Katakana(カタカナ) is that it uses the same rules Hiragana(ひらがな) does. This will make it fairly easy to learn it.

As you can see, the Katakana(カタカナ) characters resemble somehow the Hiragana(ひらがな) ones. For instance, the symbols for “ka”, ”ki”,”ku", “he”, “mo” and “ya” are very similar to its siblings from the Hiragana(ひらがな) chart.

You have to have special care with the characters for “shi” and “tsu”. They are very similar and easy to mix up.

※ In order to remember them correctly remeber this:

“shi”(シ) = the lines are horizontal

“tsu”(ツ) = the lines are vertical

As for rules, Katakana(カタカナ) uses the same rules as Hiragana(ひらがな). Stroke order and character size is key to make your writing more fluid. Remember that all your characters have to fit into an imaginary square.

I recommend the same method as for Hiragana(ひらがな) to memorize these characters. Use a college block and write a whole line of “ka’s” then you move on to “ki", "ku", "ke", "ko", ect.

This is the fastest way of storing it permanently in your brain.

Example:

カカカカカカカカカカカカカカカカカカカカカカカカ

You use dakuten(濁点) and handakuten(半濁点) for Katakana(カタカナ) as well. They work the same way and are placed similarly.

- When you add dakuten to the ka-series, these become “ga”, “gi”, “gu”, “ge”, “go”.

- When you add dakuten to the sa-series, these become “za”, “ji”, “zu”, “ze”, “zo”.

- When you add dakuten to the ta-series, these become “da”, “ji”, “dzu”, “de”, “do”.

- When you add dakuten to the ha-series, these become “ba”, “bi”, “bu”, “be”, “bo”.

- When you add handakuten(半濁点) to the ha-series, these become “pa”, “pi”, “pu”, “pe”, “po”.

Special Rules

Now that we know all the Katakana(カタカナ) syllables, we will introduce some special rules again.

※ (this time simpler)

Double consonant

In order to make a vowel sound longer, you simply have to add a long minus (ー) either between or after a character.

The vowel that comes before the long minus (ー) is extended. Just to let you know what these words mean I provided the translation of these Katakana(カタカナ) words.

Yes, that is how Japanese people spell and pronounce English and Wester words in general.

Combined syllables

Just as with Hiragana(ひらがな), you can combine the characters that end in “i” with a small “ya”, “yu”, “yo” to form a combined syllable.

You can attach the small characters of ya, yu, yo to the characters of ki, gi, shi, ji, chi, ni, hi, bi, pi, mi and ri.

※ There exist a few more special characters but I won't teach them to you for three reasons:

- Katakana is not widely used in texts and going to much into katakana will make it unnecessarily harder for you.

- You can infer the remaining special characters as they are made of the basic characters you already know.

- With what you know now about katakana, you can read 95% of the words written in katakana without problems.

Once you finish this, you are done with Katakana(カタカナ). You have all the rules you need to become a Katakana(カタカナ) reading and writing machine. If you want to improve your Katakana(カタカナ) skill, you can play a game called kana invader.

You will see Katakana(カタカナ) in literature, tv shows, advertising, on restaurant cards and on many many more places. So it will be useful.

The next lesson will be a short lesson about Kanji(漢字) and I will introduce, for the first time, some vocabulary(ごい) so you can start understanding some Japanese.

In this lesson, we will learn the basics of kanji, so you understand how kanji is build, and some vocabulary.

Kanji(漢字)

Kanji, as you might know, are imported Chinese characters. They are one of the most difficult parts of learning Japanese. That’s a miss concept. They are not hard to learn. It just takes time.

The good thing about Kanji(漢字) is that it just replaces hiragana characters. In other words, you don't have to learn new pronunciations or syllables. The bad news is that there exist around 50,000 kanji characters.

The good thing about Kanji(漢字) is that it just replaces hiragana characters. In other words, you don't have to learn new pronunciations or syllables. The bad news is that there exist around 50,000 kanji characters.

Don't panic. You don't have to learn 50,000 kanji in order to read Japanese mangas, magazines, newspaper or books. Your are considered to be a good reader with 2,000 kanji. That might sound a lot but it’s actually not that much. Just remember “it takes time” to learn kanji. That is why the resources that I mentioned earlier are so important.

The purpose of this lesson is of showing you how kanji are build and explain its characteristics so you get used to them.

Kanji(漢字) structure

Kanji is a form of writing words with less characters. As you have noticed, hiragana words can be very long. In most cases, kanji try to shorten words.

Kanji are also used to make reading faster and easier, even if you might not think so.

All kanji have two meanings: on’yomi and kun’yomi. On’yomi refers to the single reading also called Chinese reading. When you see a kanji alone then you use the on’yomi meaning(reading). Kun’yomi on the other hand refers to the attached reading, also called Japanese reading. If you see two kanji together, then you use the kun’yomi reading.

Depending on the characters there can be one to several on’yomi and kun’yomi meanings for a single kanji. To illustrate how kanji work and are structured I will provide an example.

As you can see in the image, the stand alone pronunciation is “hito(ひと)” and the attached pronunciation is “jin(じん) or “nin(にん)”. To show you how kanji behave I used it in an example.

その 人は やさしい です = Sono hito wa(は) yasashii desu.

(That person is friendly)

三人が います = Sannin ga imasu

(There are three persons)

In the first example, the kanji for person(人) is read as “hito” because it stands alone. If you add hiragana to a kanji, then you pronounce the kanji as if it stays alone as well.

In the second example, the kanji for person(人) is read as “nin” because it is attached to the kanji for three(三). We have to use the attached reading for person(人) but we use the stand alone pronunciation for three(三) because person(人) is attached to three(三) but three(三) is not attached to anything.

Kanji(漢字) purpose

Returning to the purpose of kanji. As you have seen in the example the kanji is shorter then written out words in hiragana. It is also easier to read because whenever you see the kanji for person(人) you know that it means person. You can associate kanji with complete words instead of building a word with hiragana characters.

Now kanji don't always make a word shorter. There are words that would be shorter or easier to write in hiragana. But again, it is easier to recognize a word when it is represented by kanji.

Example:

行 = い

As you can see, it would be easier to write the hiragana for i(い) then the kanji(行).

Another purpose of kanji is that it helps organize your writing. If you ever looked into a Japanese book or site, then you might have noticed that they don’t use spaces between words.

Example:

原子爆弾を起爆装置として用い、この核分裂反応で発生する放射線と超高温、超高圧を利用して、水素の同位体の重水素や三重水素(トリチウム)の核融合反応を誘発し莫大なエネルギーを放出させる

The above sentence is a sentence from a wikipedia article. As you can see, if it all were written in hiragana you might ask yourself where does one word start and end ?

With kanji you know that a word starts with a kanji and finishes either with a kanji or hiragana. This makes it easier to read words and sentences.

This should have explained to you what you need to know about Kanji(漢字).

Vocabulary(ごい)

Now that you know what you need about Kanji(漢字) we will introduce some vocabulary. Below is a list with vocabularies.

"Hajimemashite" is used when you present yourself to someone or when you start a formal conversation.

"Yoroshiku onegaishimasu" is used at the end of a presentation.

Ohayou gozaimasu is used exclusively for the morning until 10am. From there on, you have to use konnichi wa. Konnichi wa means literally “this day is” or “as for this day”. You use this greeting only for the day. Konban wa is used from the evening onwards.

Pronunciation

When you see a “shi” followed by a “te” or a "ku" you simply pronounce it “shte” or "shku" not “shite” or "shiku". So “itashimashite” is pronounced “itashimashte”.

This is our first grammar lesson. We will introduce you to Japanese Verbs. We will start explaining a bit the difference about Japanese verbs and then we will go and tackle our first Japanese verb: “desu(です)”. This verb is the Japanese version of the english “to be”.

The examples will be using Hiragana(ひらがな), Katakana(カタカナ) and Rōmaji.

The examples will be using Hiragana(ひらがな), Katakana(カタカナ) and Rōmaji.

Japanese Verbs

First off, as in any language, there are regular and irregular verbs. In Japanese, there are three types of verbs: formal, informal, irregular.

You don't have to panic. We will learn one at a time. The good news is that both formal and informal verbs have easy and solid rules. The bad news is that both formal and informal verbs have irregular verbs. Although irregular verbs exist, they are a vast minority, about (5%).

I personally think that learning all the types of verbs together is a BIG ERROR. When I tried to learn them altogether on the internet I ended up with a verb knot in my brain. The problem is that once you learn them together you will keep mixing the concepts. You will spend more time untangling concepts than learning them. So, we will start with formal verbs.

A great feature of Japanese verbs is that you don't have to match them to the person. In English, you would say: “He walks, I walk”. In Japanese, they all just “walk”. You usually have to add in English a “do, does, don't, doesn't” if you want to affirm or negate a sentence. In Japanese, there exists only “do and don't” and they are easier than you think.

Verb “to be”

Before jumping into our first verb, you have to learn the golden rule for all Japanese verbs

※ Golden rule: ALL Japanese verbs, have to go ALWAYS at the END of the sentence.

Now let’s start taking the above table apart.

Desu(です) is the Japanese version of the verb “to be”. It is not really a formal verb because it conjugates a little different than formal verbs but it is the most important verb and you get the idea of how formal verbs conjugate.

Now we will build a few simple sentences with this verb.

Example:

りんご = Ringo

(Apple)

りんご です = Ringo desu.

(It is an apple)

りんご では ありません = Ringo dewa arimasen

(It is not an apple)

りんご でした = Ringo deshita

(It was an apple)

りんご では ありません でした = Ringo dewa arimasen deshita

(It was not an apple)

You see how simple it is to form a sentence with desu(です). You don't even have to add a person to the sentence.

- Use the present positive to affirm something in the present.

- Use the past positive to affirm something in the past.

- Use the present negative to negate something in the present.

- Use the past negative to negate something in the past.

Formal verb structure

Formal Japanese verbs use almost the same structure. Actually, formal verbs use an even simpler structure than desu(です) does.

I have put a “minus” between the verb’s stem and the changing part. You can take the stem of any verb and conjugate it as shown in the table above. The stem of the verb is what comes before the “-masu”.

To form a sentence you do the same thing as you did with the desu(です) verb except that you have to add the particle “wo(を)” before the verb in order to show the direct object. We will read more about particles in our next lesson. But for now look at the examples.

Example:

たべます = tabemasu

(Eat)

りんごを たべます = Ringo tabemasu.

(I eat an apple)

りんごを たべません = Ringo tabemasen

(I do not eat an apple)

りんごを たべました = Ringo tabemashita

(I ate an apple)

りんごを たべません でした = Ringo tabemasen deshita

(I did not eat an apple)

It is quite simple isn’t it ?

Formal verbs in Japanese have a simple structure. As you can see from the above examples:

- Japanese verbs indicate whether they are positive or negative.

- Japanese verbs indicate whether they are present or past.

- Japanese verbs indicate whether they formal or informal.

With this, you can take any Japanese verb conjugate it and use it. That’s great you have archived a milestone.

Vocabulary

Now came the time to learn some more vocabulary in order to expand our Japanese arsenal.

This time the vocabulary is pretty much self explanatory. The only thing I would like to explain is that the prefix “ko(こ)” comes from “kodomo(こども)” which means kid. It is added at the beginning of an animal to make it a baby animal.

Example:

こいぬ = Ko inu

(puppy or baby dog)

こねこ = Ko neko

(kitten or baby cat)

こウサギ = Ko usagi

(kitten or baby rabbit)

This covers our lesson about Japanese formal verbs and the verb “desu(です)”. In the next lesson, we will expand our Japanese horizon with particles. This will add more dynamic to our Japanese.

※ A tip regarding the vocabulary. The best way to learn vocabulary is writing it down on a flash card or a paper. If you want to learn something you have to write it down and speak it out loud. That way your brain stores the information permanently. You don't need to repeat it to yourself a hundred times. We will be using these words in our lessons.

In the previous lesson, we learned about verbs and their importance. We even started building our first sentences in Japanese. In this lesson, we will take our sentences a step further with questions.

You may ask yourself: “How do I form a question ? Do I add a question mark at the end of the sentence ? Do I add two question marks as in Spanish ? NO.

Forming a question in Japanese is fairly simple. All you have to do is add a “ka(か)” behind the verb. In order to make it clear I will show it to you with some examples.

Check out the Hiragana and Katakana lesson if you have problems reading the examples.

Examples:

りんご ですか = Ringo desu ka.

(Is it an apple?)

りんご では ありませんか = Ringo dewa arimasen ka

(Is it not an apple?)

りんご でしたか = Ringo deshita ka

(Was it an apple?)

りんご では ありません でしたか = Ringo dewa arimasen deshita ka

(Was is it not an apple?)

As you can see, forming a question in Japanese is quite simple. You attach the “ka(か)” to the final verb and you are done. The really good thing as you can see, is that you don't have to rearrange the sentence as you do in English.

※ It is an apple => Is it an apple?

Therefore it is easier to form a question in Japanese than in English or other languages.

|

Tokyo Metro by inlovewithjapan / © Some rights reserved.

Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution license

|

Particle “GA”

You use the particle “ga(が)” in any questions that asks for who ?

Example:

だれが = dare

(who)

だれが りんごを たべましたか = dare ga ringo wo tabemashita

(who at an apple ?)

せんじさん が たべました = Senji-san ga tabemashita

(Senji ate/did)

As a matter of fact, you can use “ga” instead of “wa(は)” and still have a valid sentence. While it is true that you can use the particle “ga(が)” as a replacement for “wa(は)”, you should keep in mind that the purpose of “ga” is not to connect words and make the sentence smooth but to attract the attention of the reader/listener.

We will talk more about particles and their use in the next lesson.

For now you just have to know that questions in Japanese use a “ka(か)” at the end of the sentence and the subject is connected with the rest of the sentence with the particle “ga(が)”.

Vocabulary

For more vocabulary visit the Kanji & Vocabulary lesson.

The five Ws are pretty much self explanatory.

The suffix -san is attached to any given name to make it polite. As you might know, in Japanese culture politeness is number one. I will post a Japanese culture lesson in the coming days with some of my picture from Japan so you understand Japanese culture a little bit more.

※ Suzuki-san => Mr. Suzuki

As you can see, I only posted the present positive form of the verbs. It is up to you to conjugate them as you have learned in the previous lessons.

Out of these 3 verbs, “shimasu” is a little bit special because it does not just mean “do” but you actually use it to build verbs out of nouns. We will learn more about “shimasu” in another lesson. For now it is fine as you see it.

Important: remember the golden Japanese verb rule. Verbs go always at the end of the sentence. Although I think you remember that.

Particles

Japanese has no articles … In Japanese, they use particles instead. There are different particles for different purposes. You can look at them as connectors. We will focus on the three main particles for now which are “wa(は)”, “ga(が)” and “wo(を)”.

Particle WA

The particle wa(は) is used right after the subject of the sentence. Its equivalent in english would be “is/as for”. We have seen this particle earlier in our Kanji & Vocabulary lesson. The vocabulary konban-wa and konichi-wa use this particle. In that lesson, I explained that these vocabularies mean “as for this day/evening”. Usually you could use these vocabularies to say: “As for this day/evening it is …”. You start to understand how this particle works. We will make ourselves more familiar with this particle with a few examples.

Examples:

たべもの = tabemono

(food)

あつい = atsui

(hot/warm)

りんごは たべもの です = Ringo wa tabemono desu

(Apple is food)

こんばんは あつい です = Konban wa atsui desu

(This evening is hot/warm)

The use of this particle is fairly simple as you have noticed. You put it just right after the subject of your sentence and you are done.

※ If you like, you can a "neね" at the end of the sentence. When you add a "neね" at the end of a sentence you are looking for agreement with your statement/sentence.

Example:

こんばんは あつい ですね = Konban wa atsui desu ne

(This evening is hot/warm, isn't it ?)

Simple right ? and it adds a nice familiar feel to your sentences.

|

| Akihabara by inlovewithjapan / © Some rights reserved. Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution license |

Particle GA

The particle “gaが” has a similar use to “wa(は)”. The only difference is that you use “ga(が)” to emphasis a sentence. Usually you use it for questions that ask for who or what. You use this particles in these questions because you want the subject of your question to stand out. You tag it right behind the subject because it has to mark the subject of your sentence just as you did with “wa(は)”. We have seen this particle in the previous lesson.

example:

だれ = dare

(who ?)

だれが りんごを たべましたか= dare ga ringo wo tabemashita

(who at an apple ?)

せんじさん が たべました = Senji-san ga tabemashita

(Senji ate/did)

You should keep in mind that the purpose of “ga(が)” is not to connect words and make the sentence smooth but to attract the attention of the reader/listener to the subject.

Using “ga(が)” in sentence were you should use “wa(は)” is not grammatically wrong. If your subject is the main point of your sentence, use “ga(が)”. If not, use “wa”.

Summary:

- Use “ga(が)” to emphasis the subject of the sentence.

- Use “ga(が)” for questions with who or what

- Use “ga(が)” to answer questions with who or what

Particle WO

I have mentioned in our first lesson that the hiragana character “wo(を)” is exclusively used for grammatical purposes. In fact, it is a particle. To make it simple:

- The particle “wo(を)" marks the object that is being affected by the verb.

The object that is being affected by the verb is simple to recognize. It is also called the Direct Object (DO). To illustrate how simple it is to find the Direct Object of the sentence we will look at some examples:

- I read a book => Direct Object = book

- Jim ate a sandwich => Direct Object = sandwich

As you can see in the example, the book/sandwich is affected by the action of the verb in this case read/ate. In Japanese you have to make this clear by tagging the particle “wo(を)” to your direct object.

Example:

ほん = Hon

(book)

せんじさんは たべました = Senji-san tabemashita

(Senji ate)

せんじさんは りんごを たべました = Senji-san wa ringo wo tabemashita

(Senji ate an apple)

せんじさんは ほんを よみましたか = Senji-san wa hon wo yomimashita ka

(Did Senji read a book ?)

As you can see, it is quite simple. It may take some time to adapt this habit but once you do, it becomes a peace of cake.

Vocabulary

The vocabulary for person, hot / warm and cold are simple an self explanatory. You can use these to make your own sentences with the particle “wa(は)” and “ga(が)”.

The vocabulary for month and day are small intro to time in Japanese. In the coming lesson we will learn more about Japanese time and another particle that will help us tell the time.

I provided the vocabulary "nan" so you can build your own sentences with it and the particle “ga(が)”.

Book, Newspaper and Light novel are object you can use to practice the particle “wo(を)”.

I would like to point out that the vocabulary I provide is very simple. It is up to you to do more research. I recommend downloading a Japanese book from Aozora Bunko for free and then pick some words randomly.

In order to learn these particles, you have to build your own sentences with them. They don't have to be fancy.

This will be one of the simplest Japanese lessons. We will start with some numbers vocabulary and then move on to the numbers structure.

I provide the Kanji of these numbers so you get used to them. Later I will provide Kanji flashcards with their kun’yomi and on’yomi meaning.

I think that the vocabulary table is pretty much self-explanatory. I just would like to explain the little confusion you might have with “4”, “7” and “9”. It is simple. You can use both meanings, but the one in between the brackets is used less often.

You use the one in the brackets for combined meanings (July = Shichi-gatsu) but you don't have to worry about that yet.

You use the one in the brackets for combined meanings (July = Shichi-gatsu) but you don't have to worry about that yet.

Great, so now we can count from 1-10 but what comes next ?

To count from ten upwards, you simply combine ten with the number you need. You can do this until you reach 19.

Example:

じゅう いち = Juu ichi

(ten + one (11))

じゅう に = Juu ni

(ten + two (12))

When you want to count 20, 30, 40, etc. You simply put one, two, three, etc. in front of ten.

Example:

に じゅう = Ni Juu

(two x ten (20))

さん じゅう = San Juu

(three x ten (30))

よんじゅうよん = Yon Juu Yon

(four x ten + four (44))

※ Keep in mind that you have to use “yon” not “shi”, “nana” not “shichi” and “kyuu” not “ku”.

In other words, you multiply what goes before ten and you add what goes behind ten.

- 2 x 10 = 20

- 2 x 10 + 1 = 21

Great now we can count until 99. What about 100 and above ?

As you can see, it is as simple as counting from 1-99. One hundred means “hyaku”. To count upwards, you simply add numbers from 2-9 before “hyaku”. You have to take special care with “300”, “600” and “800”. They are different because in Japanese they think that it is easier to pronounce them like this.

If you want to tell a number between hundreds, you simply attach what we did earlier to the hundred.

Example:

ひゃく よんじゅう よん = Hyaku Yon Juu Yon

(100, 4, 10, 4 (144))

さんびゃく ごじゅう さん = San byaku Go Juu San

(300, 5, 10, 3 (353))

Again, you use the same logic as with ten. You multiply what goes in front of “100” and add what goes behind it.

- 3 x 100 + 5 x 10 = 350

- 100 + 3 x 10 + 5 + 135

In the “1000” group, you use the same pattern as before. Just pay attention to “san zen” and “has sen”.

Again, for numbers in between you simply attach what we did so far.

Example:

せん ひゃく よんじゅう よん = Sen Hyaku Yon Juu Yon

( 1000, 100, 4, 10, 4 (1144))

はっせんさんびゃく ごじゅう さん = Has sen San byaku Go Juu San

(8000, 300, 5, 10, 3 (8353))

Now we are done with the “1000” group and we can count until “9999”. We are done with the most complicated part of counting. Now, we finish with the “10,000” group.

This group is simple because there are no exceptions nor special pronunciations. You simply attach a number before “man” and you are done.

※ Only one exception: You have to attach “ichi” to “man” in order to say “10,000”. “Man” alone is not enough.

example:

いち まん = Ichi man

(1 x 10,000 (10,000))

に まん = Ni man

(2 x 10,000 (20,000))

じゅう まん = Juu man

(10 x 10,000 (100,000))

ひゃく まん = Hyaku man

(100 x 10,000 (1,000,000))

せん まん = Sen man

(1000 x 10,000 (10,000,000))

Congratulation, you can now count until 10,000,000. You have reached a new milestone in your Japanese learning path. You may be asking yourself why do I have to count so high? These numbers are mainly used for money and as you might know “100 yen” equals roughly “$1”. So, “10,000,000 yen” equals roughly “$100,000”. If you are going to spend more than this, you probably shouldn't use this guide and go pay for a Japanese teacher (little joke). Many prices in Japan are in the “hyaku” to “sen” range.

So when you want to buy a “PS Vita-2000” and the Cashier says:

- はい、いちまん きゅうせん ひゃく にじゅ えん です。

※ えん (円) = Yen (¥)

You know that he is saying that it costs ¥19,120. ($182 minus taxes)

※ Study Tip: Count, Count and Count. Start counting from 1-99. Then count the hundreds, the thousands and the ten thousands. Finally Pronounce random numbers. You use pieces of paper and write numbers from 1- 10,000,000 on them. Then you put them facedown or in a box and pronounce the random picked numbers.

Particle NI (に)

In the particles lesson and up until now, we have always used only three particles: wa, ga, wo. Today, we will expand our particle horizon with ni(に).

In Japanese, the particle ni(に) has several purposes like directions and time. Officially, it is called an indirect object marker but that definition makes it just confusing.

What it does is, it indicates where something is and who did what to who. It basically shows the direction of an action nothing more. Its english cousin would be “to” but it also has several other cousins which we will learn later on more about.

|

| "Tamatsukuri onsen yado02s3648" by 663highland - Own work. Licensed under CC BY 2.5 via Wikimedia Commons. |

Vocabulary

Since directions need places we will learn some vocabulary with a little vocabulary charts of common places.

The vocabulary is straightforward. Japanese people have separate words for Japanese style Hotels (Japanese Inn) and Western style hotels. Japanese Inn (りょかん) have a Shōwa era style. They are very classic and give you a feeling like you traveled back in time. The workers are dressed in kimonos, the rooms have tatami floors and futons.

The only vocabulary I would like to explain is the Shop suffix (ーや). It works very simple. You simply attach it to a noun and it will turn that noun into a store.

Example :

We have learned in the Particles Lesson the word for Book (ほん).

ほん = Hon

(Book)

ほんや = Hon ya

(Book Store)

はな = Hana

(Flower)

はなや = Hana ya

(Florist/ Flower Shop)

You see, simple isn’t it ?

Particle NI (に) & Places

Now that we know some vocabulary and a little bit about what this particle does, we can start learning how to use it for places.

All you have to do is tag it after a word or place in this case. The simplest way to use it is by putting it between your word(place) and the verb. An interesting thing about Japanese is that sentences are made of blocks. These blocks can be rearranged as you will see in the coming examples.

Example:

(1) がっこうに いきます = gakko ni ikimasu

(I go to school)

(2) えきに いきません でした = eki ni ikimasen deshita

(I didn’t go to the train station)

As you have noticed until now, there is no need to put an “I” in the sentence because it is assumed you are talking about yourself. This only changes when you talk about somebody else.

Example:

(3) せんじさんは えきに いきました = Senji-san ha eki ni ikimashita

(Senji went to the train station)

For now all you have to do is to attach the particle to your word(place) and add a verb to describe the action.

This particle is quite simple isn’t it ?

Block nature

Now, I have written about “blocks” that can be rearranged a little earlier. Can you recognize these “blocks” in the first two examples ?

※ Tip: Remember that the verb has to go always at the end of the sentence.

In the first two examples there were two “blocks”.

Block 1: がっこうに || えきに

(gakko ni) (eki ni)

Block 2: いきます || いきません でした

(ikimasu) (ikimasen deshita)

Example 3 is a little bit different because we have a person in it. The “blocks” for example three are still easy to figure out.

Block 1: えきに

(eki ni)

Block 2: いきました

(ikimasu)

Block 3: せんじさんは

(senji-san ha)

In the first two examples, it was easy to figure out the “blocks” but the last example was a bit tricky. “せんじさんは(Senji-san ha)” is a “block” by itself.

Now, lets see how we can rearrange our “blocks”. The first two examples have just two “blocks” of which one(the verb) has to go at the end of the sentence. So, we are left with the last example which can be rearranged as follows:

えきに せんじさんは いきました = eki ni senji-san ha ikimashita

(Senji went to the station)

As you can see, the meaning is the same the only difference is that the order changed. The reason I'm showing this to you is not to confuse you. I personally don't like rearranging blocks but it is necessary to recognize them and understand them. That way when you encounter them one day you understand what it means.

For Anime Fans

Here is another example for the anime fans. You may remember Monkey D. Luffy’s famous phrase in One Piece: “I will become the Pirate King”. As of now, we would say it like this:

おれは かいぞくおう に なる = Ore ha kaizoku ou ni naru

(I will become the Pirate King)

But he actually rearranges the blocks like this:

かいぞくおう に おれは なる = Kaizoku ou ni ore ha naru

(I will become the Pirate King)

The three blocks in this case are “かいぞくおう に(kaizoku ou ni)” , “おれは(ore ha)”, “なる (naru)”.

※ Vocabulary check: Please keep in mind that “KAIZOKU” is Pirate and “KAZOKU” is Family. They sound very similar so keep this in mind.

Blocks with "wo"

It is important to note that the block that actually moves is the "place & NI" block. The rest stays as it is.

In the case of the particle "wo", it is a simple extension of the verb. Your object is attached to the verb with this particle. It means that you don't move the "verb block". To illustrate this, here is an example:

せんじさんは にほんに ほんを よみます = Senji-san ha nihon ni hon wo yomimasu

(Senji reads a book in Japan)

にほんに せんじさんは ほんを よみます = nihon ni Senji-san ha hon wo yomimasu

(Senji reads a book in Japan)

Now, this is actually a bit beyond just telling direction but it this shows you how the block nature applies to the particle "wo".

This should be enough for this lesson. You can feel happy and proud because with this you have archived another milestone in your Japanese journey.

Remember to make your own sentence with this new knowledge and keep in mind that monologues help you practice your knowledge as well.

Our last Particle

In our everyday conversations, one of our basic needs is "possession".

We always say what belongs to us and what does not. In english, we usually use either the apostrophe " 's " to do so or "of".

There are other options as well. But in Japanese, there is only one way to show possession and that is with the particle NO.

The Particle NO

In Japanese, the particle NO is a connector. In a sentence, you put the Owner first followed by the particle NO and the object. It is a very simple particle and very useful.

Owner + NO(の) + Object = Possession

Example:

わたしの いぬ = Watashi no Inu

(My dog)

わたしの いぬ です = Watashi no Inu desu

(It is my dog)

せんじさんの いえ = Senji-san no ie

(Senji's house)

せんじさんの いえ です = Senji-san no ie desu

(It is Senji's house)

せんじさんの いえ ですか = Senji-san no ie desu ka

(Is it Senji's house ?)

きみの もの ですか = Kimi no mono desu ka

(Is this your thing ?/ Is this yours?)

In the last example, "kimi (きみ)" means "you" but with the particle it becomes "yours". You can also use "anta (あなた)". The noun "mono (もの)" means "thing" but when you use it in a sentence it has a different feel to it: Kimi no mono desu ka => Is this yours?

Pretty simple so far. You might have noticed that in the first example "Watashi no" doesn't mean "I" but "my". Japanese is very convenient in this. "Watashi no" means "my". "Anata no" means "yours" in English. The particle NO makes the difference. "Watashi" and "Anata" change automatically from "I" and "you" to "My" and "Yours" because of this particle.

Example:

わたし = Watashi

(I)

わたしの = Watashi no

(My)

あなた = Anata

(You)

あなたの = Anata no

(Yours)

So far so good. Keep in mind that the order never is reversed as in English. In English, you could say "The driver of the Hotel" but in Japanese the order is not altered.

Examples:

The driver of the Hotel

うんてんしゅ(運転手) = Untensha

(driver)

ホテルの うんてんしゅ(運転手) = Hoteru no Untenshu

(The Hotel's driver / The driver of the Hotel)

This is what makes this particle so simple. It doesn't alter its order. You always use it the same way.

Vocabulary

テーブル, ベッド and コンピュータ are words borrowed from English that is why they are written in Katakana and not in Hiragana. Other than that, the list is very simple and contains some common objects you can use to practice with the particle NO.

No this ends our Japanese crash course if have any doubt read it over again and pay attention to the resources as they are very important to learn Japanese.

No this ends our Japanese crash course if have any doubt read it over again and pay attention to the resources as they are very important to learn Japanese.